Insights Post

Thursday’s UK local elections: A risk for GBP

Most of the United Kingdom – England, Wales, and Scotland – go to the polls on Thursday for UK local elections. The elections will be important for the markets for two reasons:

- They will provide the first real reading on the Conservative Party’s popularity since the December 2019 General Election. Was the party’s breakthrough performance in the North, a traditional Labour stronghold, a one-off due to Brexit, or did it signal a lasting realignment of UK politics? And

- They may be the first step toward independence for Scotland. That could be a crucial matter for the pound.

The latter issue is more important for the markets, so let’s discuss that first.

The last time Scotland voted on independence, in 2014, the “no” side won 55.3% to 44.7%. But that was before Britain – or, shall I say, England and Wales – voted in 2016 to leave the EU. Scotland voted “remain” 62% to 38% (as did Northern Ireland, 56% to 44%). Since then, Scotland has been wondering whether its interests lie more with England, which they’ve been in union with since 1707, or with the much bigger EU.

Pro-independence parties have been pushing for a re-run of the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. If these parties win a majority in Thursday’s local election, they are pledged to start working toward such a vote.

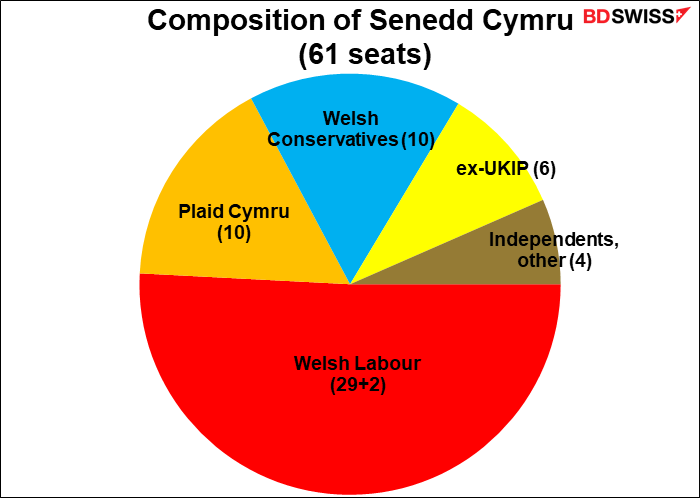

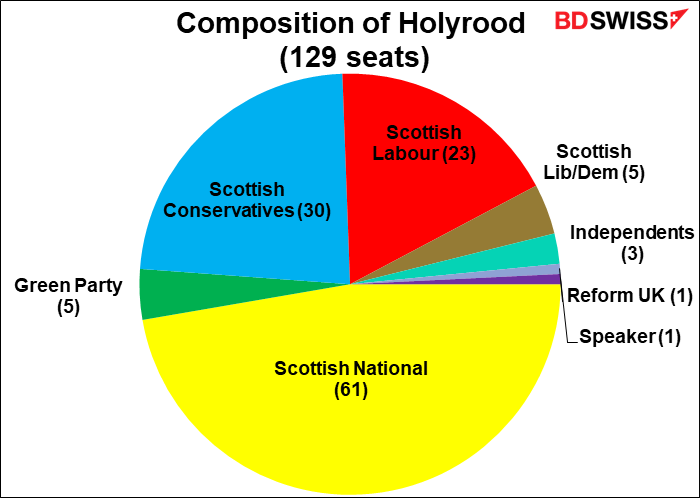

Currently, the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) is the largest party in the Scottish Parliament, known as Holyrood. It governs in coalition with the Greens, another pro-independence party.

The election is for 73 constituent seats and 56 regional seats. It’s an incredibly complicated voting system designed so that the more constituent seats a party wins, the harder it is for them to gain regional seats.

In any case, recent polling suggests the pro-independence SNP is likely to win a majority on its own, and if it doesn’t, the Green Party is forecast to win 10 seats, so that should put the two of them over the top. And then there’s the new Alba Party, a spin-off from the SNP, which is also pro-independence. On the other hand, the three major national parties – the Scottish Conservatives, Scottish Labour Party, and the Scottish Liberal Democrats — will be actively campaigning against independence.

Voting closes at 2200 GMT, but because of the pandemic the counting won’t begin until Friday morning, which means the result is likely to come out over the weekend, when financial markets are closed.

How to achieve independence

It would take three steps for Scotland to start on he road to independence:

- Pro-independence parties win the election – that looks pretty certain now. It didn’t last week, but the latest polls suggest the SNP is likely to win a majority by itself, and if not, it will almost certainly be able to govern again in coalition with the Greens.

- The UK Parliament would have to grant permission for a new referendum. Unlikely. PM Johnson opposes it, and he has a majority in Parliament. The Government argues that politicians should concentrate on recovering rebuilding the economy after the pandemic. The Telegraph reported that Johnson would take the SNP to the UK Supreme Court to deny prevent the party from unilaterally holding a referendum. Nonetheless, there may be some pressure to allow it. A recent survey found that 41% of UK voters think Johnson should allow another vote within four years if pro-independence parties win a majority, vs 33% who oppose and 26% “don’t knows.” Another poll, by Ipsos MORI, found 51% in favor, 40% opposed.

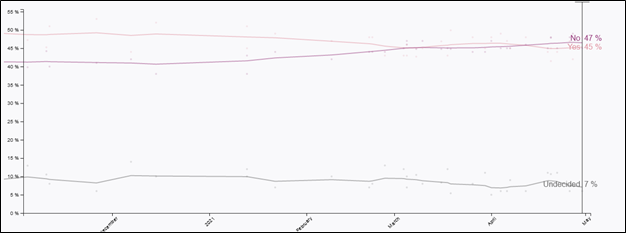

- Finally, the “leave” side would have to win the referendum, which is also debatable – they lost in 2014 and recent opinion polls show a small plurality (47% to 45%) against independence. But with 7% of the voters undecided, it’s still up in the air and a risk to sterling.

Politico’s Poll of Polls on Scotland independence

What would independence mean for Scotland?

Before there’s even a referendum it’s a bit early to be discussing what independence might mean for Scotland. I just want to highlight some of the major issues here:

- Rejoining the EU: The main impetus for another independence vote now is to allow Scotland to rejoin the EU. However, that’s not so simple. A country has to meet various requirements before they can join. Since 1972, ascension negotiations have taken an average of five years. And would Scotland be accepted at the end of it all? Under Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union, which establishes how a country can join the EU, the applicant has to be unanimously approved by the Council of the EU. I could easily see Spain vetoing Scotland to dissuade Catalonia from trying something similar. Then-EC President Jose Manuel Barroso said in 2014 that Scotland joining the EU would be “extremely difficult, if not impossible” because of this issue. Spain has yet to recognize Kosovo, for example.

- What currency would the new country use? This is of crucial importance, because in the 2014 referendum, over half of the “No” voters cited “the pound” as one of their main reasons for voting against independence. This was the biggest single reason for voting “No.” Then, the “Yes” side argued that an independent Scotland could join in a currency union with the rest of the UK, but the rest of the UK has rejected that idea. Furthermore, a country in a currency union wouldn’t be able to join the EU, the SNP now plans to replace the pound with a Scottish currency “as soon as practicable.” Either way it’s hard: using sterling without being in a currency union means no lender of last resort and no say in monetary policy, while establishing a new currency with an independent central bank requires meeting various standards for fiscal sustainability, central bank credibility, FX reserves, international trade, etc.

- How do divide up the UK’s debts: A newly independent Scotland would have to be responsible for some of the UK’s existing debt. How much? Do they divide it up on a per-capita basis or relative to GDP? How to account for North Sea oil? Either way, Scotland would start with a relatively high debt-to-GDP ratio.

- Fiscal sustainability: Scotland has run a substantial fiscal deficit over the past decade that has been covered by the central government in London. The nation’s budget deficit in FY18/19 was 7.4% of GDP, rising to 8.6% of GDP in FY19/20 or around 6 percentage points higher than the UK as a whole. The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimated that this might be some 26%-28% of GDP in FY20/21, due to the pandemic. Moreover, the North Sea oil and gas is rapidly depleting. An independent Scotland would either have to borrow heavily, pushing up interest rates, or embark on a strict austerity program. Neither is particularly popular.

- Trade Scotland currently runs a substantial trade deficit if oil is excluded. Moreover, its trade is overwhelmingly with the rest of the UK – 60.1% vs 18.3% to the EU. According to the London School of Economics’ Centre for Economic Performance (CEP), this is much more than would be expected simply by proximity to the market, no doubt because the two nations have been in a union for some 300 years. However the EU would require a “hard border” between Scotland and England for Scotland to join the EU. The kind of halfway-house that Northern Ireland arranged was a unique accommodation to ensure the viability of the Good Friday Agreement and would not be available to Scotland. The CEP’s analysis concludes that this border “would be two to three times more costly for the Scottish economy than the impact of Brexit.” “The trade-related costs of independence are similar regardless of whether Scotland rejoins the EU, since the benefits of lowering trade barriers with the EU by rejoining are roughly offset by the costs of putting the EU’s external border between Scotland and the rest of the UK.”

In sum, one wonders how a country with a large debt burden, gaping fiscal deficit, perennial trade deficit and depleting natural resources will make it on its own. However, as we saw with Brexit, economic arguments aren’t always #1 in peoples’ minds.

Impact of Scottish independence on the rest of Britain.

The impact of Scottish independence on the pound doesn’t depend on the effect that independence would have on Scotland, however. It depends on how it would affect the rest of Britain. One might argue that given Scotland’s large budget deficit, which has to be covered by the rest of the Union, Scottish independence might be a net positive for the remaining nations. However, the reduction in trade is a net drag on the rest of the UK, albeit much smaller than for Scotland. The CEP estimates that rest-of-UK income per capita falls by between 0.2% – 0.4%, depending on how the border is established. This is much smaller than the 4.2%-6.3% per capita decline in incomes that they forecast for Scotland, since trade between Scotland and the rest of the UK accounts for 44% of Scotland’s trade vs only 3.9% the other way.

Britain would also lose North Sea oil revenues, although those have been declining for many years now and are no longer the market-moving factor that they were in the 1980s.

But the biggest factor in my view would be the impetus that Scottish independence would give to Northern Ireland (NI) leaving the UK, too. Northern Ireland also voted to stay in the EU, and of course many (but by no means all, or even a majority) of its residents would actively prefer to join with the Republic of Ireland. Geographically, NI is closer to Scotland than to Wales, and the Unionists in NI (those who want to remain in the United Kingdom) are generally descendants of Scots. Scotland leaving the Union would therefore “undermine what it means to be a unionist”, says Donnacha Ó Beacháin, Associate Professor of Politics at Dublin City University’s School of Law & Government. “Ultimately, that’s the core of the identity of being a Unionist – but if the union no longer exists, you’re being loyal to a cause that is no longer there, you become a living anachronism in a way,” he said.

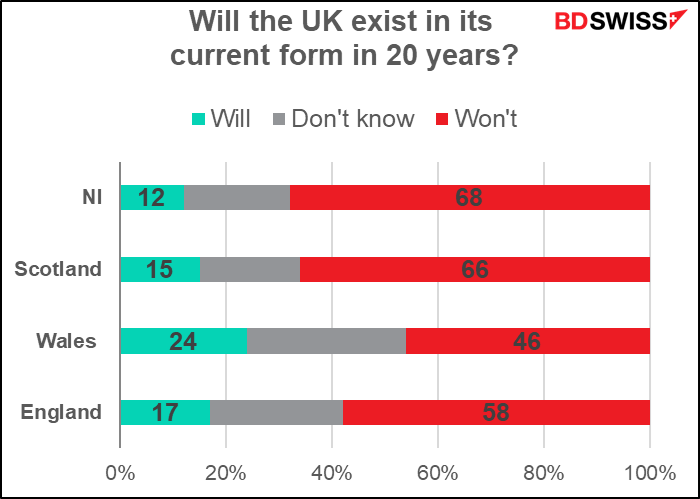

According to the above Ipsos MORI poll, the Northern Irish are the most in favor of allowing an independence referendum in Scotland (66% in favor vs 51% nationally) and the least opposed to Scottish independence (35% opposed, 30% in favor, vs 50%-17% nationally). The Northern Irish also are slightly more convinced than even the Scots that the UK won’t exist in its current form in 20 years (68% NI vs 66% Scotland and 58% nationally)

There’s no doubt that just England and Wales together would be a much-reduced country, with less trade leading to slower productivity growth, a lower standard of living, and a weaker economy. That suggests a weaker currency, too.

Short-term impact on the pound

Even if the SNP and other parties in favor of “leave” win Thursday, there are still further hurdles to leap. I think the risk of all three events happening is relatively low. Nonetheless, given the surprise “leave” vote in the 2016 Brexit referendum, we clearly can’t dismiss the possibility. I think Thursday’s vote is likely to be a short-term risk event for sterling.

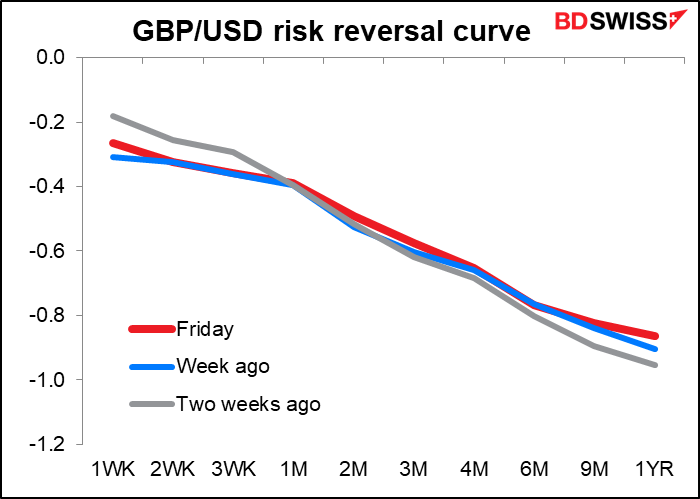

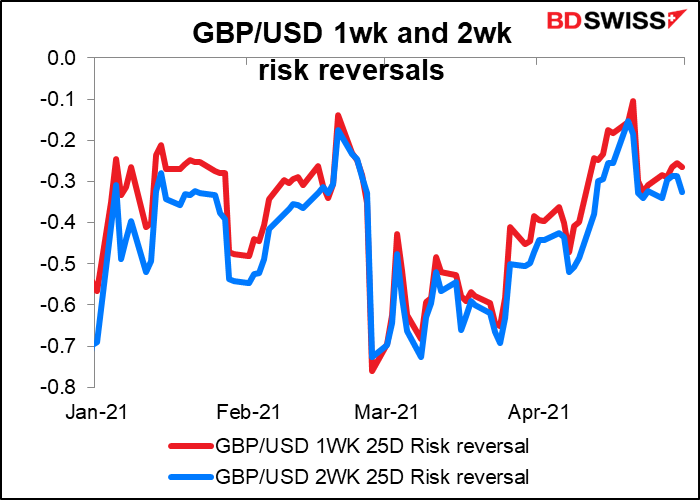

The market doesn’t seem to be worried, though. There’s been no big change in the risk reversals as the election draws near.

If anything, the perceived risk in GBP/USD has been declining recently. EUR/GBP is the same.

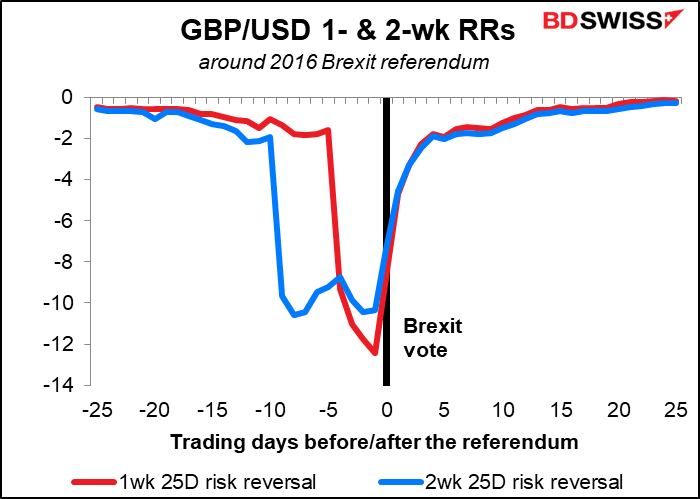

By comparison, the two-week RR started falling considerably two weeks before the Brexit vote, while the one-week RR started falling one week before, as would be expected.

Apparently the market thinks that Scottish independence is such a long shot that it isn’t even worth hedging against. I’m not so sure. Even if the ultimate outcome is highly uncertain, uncertainty is likely (if that makes sense).

Wales: The vote in Wales is not as important for now, but it bears watching. Support for independence in Wales is only about 25%, but that’s double what it was a few years ago. The main pro-independence party in Wales, Plaid Cymru, want to hold an independence referendum by 2026 if they are the largest party in the Senedd Cymru – the Welsh Parliament — but recent polling makes this seem unlikely. Labour, which have been in government since 1999, appear set to be the largest party yet again, even if they don’t win a majority of 31 seats.